[ad_1]

WeWork, the struggling communal office space company, is expected to attempt to go public this year, after the company’s first attempt was scuttled in 2019.

Marie Altaffer / AP

hide caption

toggle legend

Marie Altaffer / AP

WeWork, the struggling communal office space company, is expected to attempt to go public this year, after the company’s first attempt was scuttled in 2019.

Marie Altaffer / AP

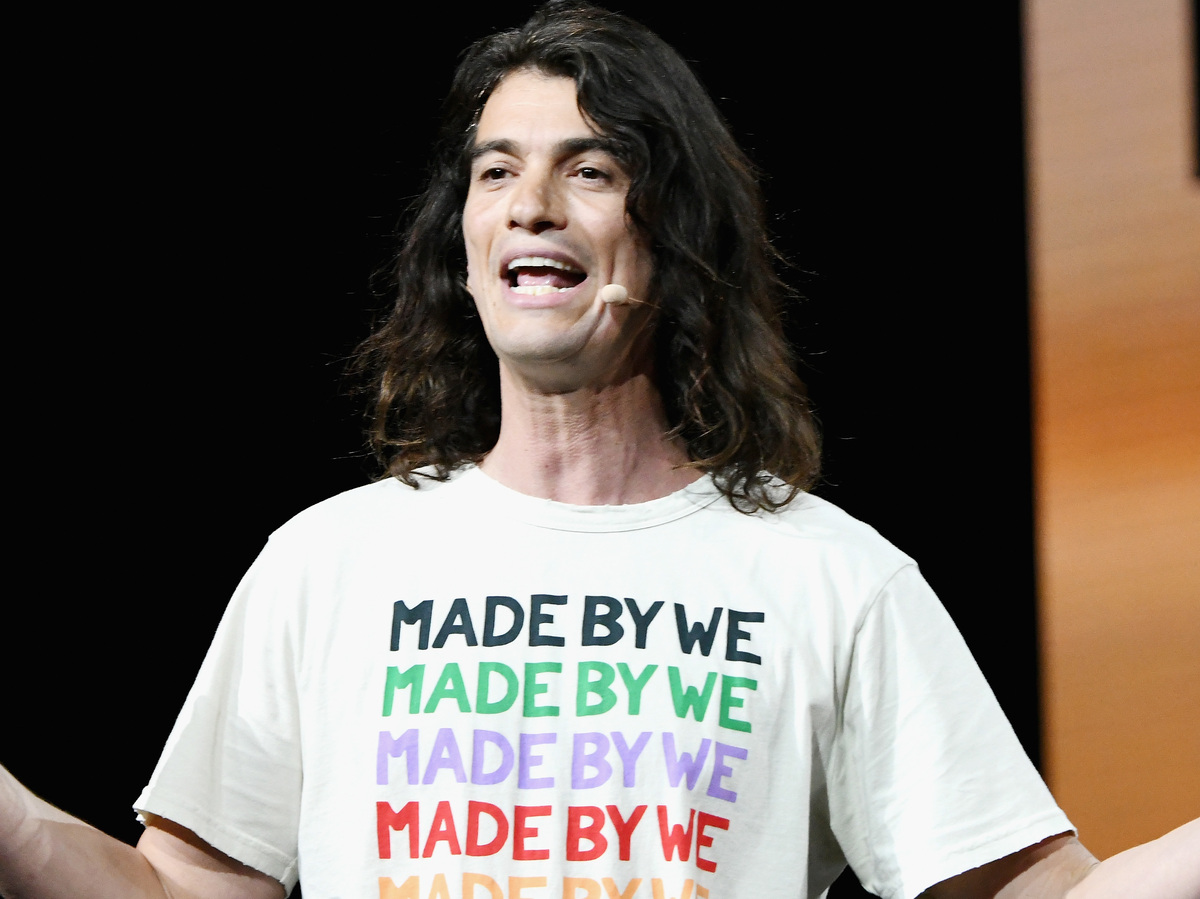

Say WeWork and one person comes to mind: Adam Neumann, the gangly founder and former CEO with flowing black hair and a rock star character who would go on to talk about the “energy” of the company’s shared workspaces. .

He’s also adopted a “party animal lifestyle,” said Eliot Brown, whose new book with co-author Maureen Farrell, The Cult of We: WeWork and the great illusion of start-ups, was released on Tuesday.

Long before noon, Neumann was known to offer potential investors shots of tequila from a bottle he kept behind his desk.

“He had installed a cigar bar type vent in his office to suck in the marijuana smoke,” Brown said in an interview.

What came out of the mist? A company that, according to investors, from the Japanese juggernaut SoftBank to large American companies like Goldman Sachs, was worth $ 47 billion.

“He created the most valuable startup in the country, but it was basically just a mirage,” Brown said. A mirage that finally disintegrated.

Now WeWork is in the middle of a second act. After dropping out of Neumann, the company hired a seasoned real estate manager as CEO and downsized its operations. He’s making a big bet on the rise of remote working and plans to go public this year, after the first attempt in 2019 under Neumann ended in a debacle.

From “the dumpster fire” to “the recovery of the ship”

Here’s how WeWork’s business model is supposed to work: Get a good deal on long-term office leases, then make a profit by subletting the spaces on short-term contracts, mostly to freelancers, gig workers. and other creatives.

But Neumann saw the mission “in almost messianic terms,” Brown said. “He thought this was going to be a business that would change the world, the most valuable business in the world, a business that would play a role in geopolitics.”

He left mundane but essential questions unanswered, such as: How would WeWork ensure that all that office space is occupied for years to come? What if a recession hits?

When WeWork first published his papers to go public in 2019, a “dumpster fire” emerged, Brown said. It turned out that Neumann had withdrawn hundreds of millions of dollars for himself; he had restructured the company to give himself tax relief; and he had rented his own properties from WeWork.

Adam Neumann speaks on stage at a WeWork event in 2019.

Michael Kovac / Getty Images for WeWork

hide caption

toggle legend

Michael Kovac / Getty Images for WeWork

Adam Neumann speaks on stage at a WeWork event in 2019.

Michael Kovac / Getty Images for WeWork

As investors, journalists and others scrutinized the company, its valuation continued to decline. He almost went bankrupt.

Today, WeWork has a new boss: former director of real estate Sandeep Mathrani. And his path is familiar in Silicon Valley. Like Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, he’s the adult who cleans up the mess left by a mercurial founder. In an apparition this spring on CNBC, Mathrani was asked about Neumann.

“It’s noise in the background as far as I’m concerned,” he replied. “My goal is to right this ship.”

WeWork Act Two: Admit It’s a Real Estate Company

These waters now seem choppy. Many employers have sent workers home during the pandemic. Some are now making these arrangements permanent, at least to some extent. This has led companies to cancel some office leases and reduce others, said Barbara Denham, an economist at Oxford Economics.

“This is one of the most uncertain times for the office market, probably since the 1970s, when so many companies left the big cities,” she said.

WeWork has also downsized. In the past two months alone, he has left 17 buildings and renegotiated the leases of more than 50 others, according to a spokesperson for the company.

But Denham says the company, which offers space literally on the hour, is well positioned to take advantage of the changing nature of office work.

“The demand for the world’s WeWorks, coworking space, the flexible office rental market, is huge,” she said.

On the flip side, Brown notes, if more people return to the office, WeWork could struggle to maintain its hundreds of leases around the world.

“WeWork is positioned as a company that capitalizes on the changing world of office space, but they really don’t know it and neither do we,” Brown said.

WeWork is also drawing its attention to people like Sameer Kapur, a student at Lost University who started a startup aimed at helping students learn to code. Right now, he’s working from a WeWork space inside a downtown San Francisco skyscraper.

“I can see other founders, see other people working. Never know who you are going to meet,” Kapur said.

It also gets stunning views; kombucha on tap; even corners to take a nap. (WeWork spaces tend to have the vibe of a Brooklyn cafe or, like The New York Times Put the, “decor inspired by gentrification.”)

But if something else happened, Kapur said, it would be nice to ditch WeWork.

“I have no brand loyalty,” he said. “If there was a cheaper alternative with so many locations I’d be happy to go with them.”

Neumann’s second act: Still in real estate

WeWork no longer says its goal is to “raise awareness of the world.” He now admits that it is indeed a real estate company – which critics of the company, despite Neumann’s objections, have said since its founding.

After WeWork’s implosion, Neumann and his wife Rebekah moved to Tel Aviv. Now, they are back in the United States, living with their six children in the Hamptons.

And Neumann starts again, would have invest in various startups related to the world of real estate.

“His goal would be the future of life,” wrote Brown and Farrell in their book. “He was impatient and full of energy. He couldn’t wait to get back into the game.”

[ad_2]

Source Link